by Barbara White, Paint Brancher

November 27, 2005

Paint Branch Unitarian Universalist Church, Adelphi, MD

(The Rainbow Crucifixion is also the title of a painting Barbara used for her masters thesis)

Shortly after I started attending Paint Branch, I participated in an interview process that was part of “Imagine Paint Branch.” One of the interview questions was – What did you like about Paint Branch the first time you attended? I was interviewing Jan Montville that day and will never forget her response to that question. She said, “I loved this meeting space, the natural surroundings, the windows at the front of this room, but most of all I appreciated the fact that there was not a dead man on a cross”. I knew I was home.

As mentioned in my introduction, I spent five years in the Episcopal Church before coming to Paint Branch and 10 years as a UU before that. What was not mentioned was that I was raised Presbyterian in Alabama. I was taught from a very early age that humankind was redeemed through the sacrificial death of Jesus on the cross. On Sundays, I heard about the self- sacrificing love of Christ who suffered in obedience to his Father’s will and that his suffering and death on the cross was redemptive. He suffered and died to save us all. Abraham only attempted the sacrifice of his son Isaac, but according to Christian theology, God allowed (and Jesus chose) death on the cross. Divine child abuse was presented as a way to redemption and the child who suffers was praised as the hope of the world.

To me, these Christian teachings sanctioned the abuse and violence in my family of origin. My father, an elder in the Presbyterian Church, routinely abused my mother, my siblings, and me. Divine sacrifice became a model and consolation for me and allowed me to discern meaning in something that was otherwise incomprehensible.

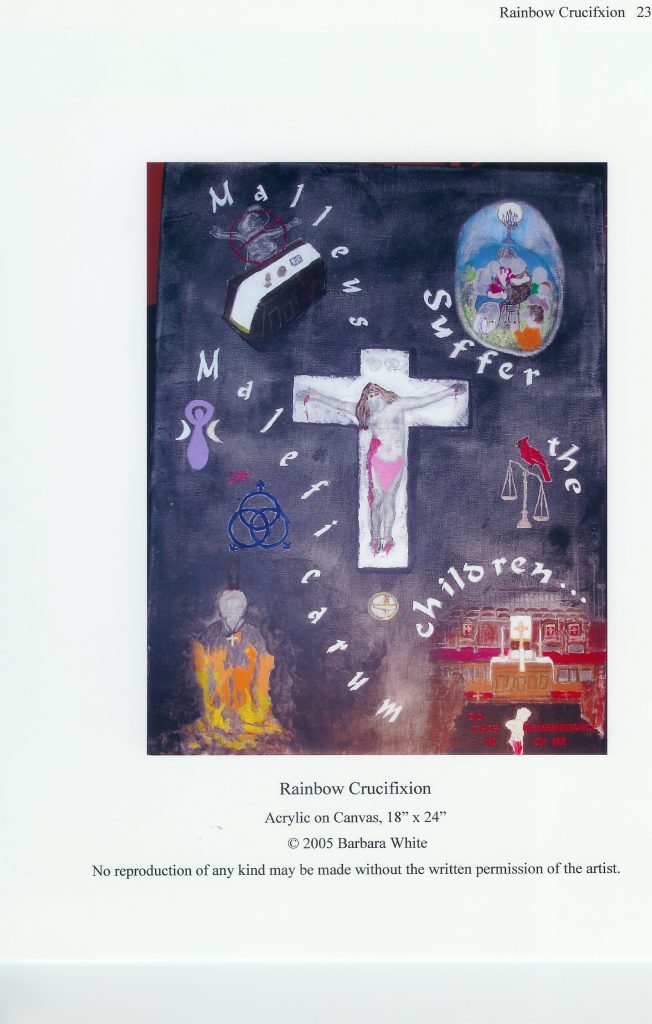

As I became an adult, however, it became clear that blood atonement theology was not the only issue. Some Christian churches engage in behaviors that add to the suffering of others. For example, Cardinal Law is included in my painting for his complicity in the abuse of so many children in the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Boston. In April of 2005, the Vatican honored him by having him preside at one of the Masses that took place after death of Pope John Paul II while survivors of sexual abuse by Catholic priests protested in St Peter’s Square.

Sexual abuse survivors are not the only populations that are oppressed and denied justice by the Church, however. Millions of gay and lesbian people have been oppressed by many (if not most) churches from within the Christian tradition that all too often reject the legitimacy of our lives and relationships. To highlight the importance of this denial and rejection, I painted the central figure on the cross with a rainbow headband and a pink triangle loincloth. As many of you know, both the rainbow and pink triangle are international symbols of the gay/lesbian/bisexual/transgendered community. Our transgendered daughter-in-law was my model for this figure.

The suffering of sexual abuse and the denial of sexual diversity by most Christian denominations are realities I know only too well and as I became an adult the consolation of a theology of “suffering victim” began to wear thin. I became frustrated in my efforts to wear theological “shoes” that no longer fit.

However, a few years ago while on vacation I encountered a print of Marc Chagall’s painting the White Crucifixion. It touched something deep within my shattered soul that I knew was important but that I was not able to articulate at the time. What I have since come to understand and articulate is that the painting depicts a world of unleashed terror (much like the world of my childhood), within which no saving voice can be heard nor any redeeming signs perceived. Chagall’s Jesus is no rescuer. He hangs powerless before the terror and suffering, another victim of violence and abuse.

It was this portrayal of Jesus as another innocent victim that challenged my thoughts regarding Christian teachings about suffering and redemption that I had heard my entire life. At the time that I encountered Chagall’s White Crucifixion, I was in the M.A. program at Loyola working on a degree in Spiritual and Pastoral Care. Confronting traditional theology in my program at Loyola and the synergy of that program coupled with my experience in spiritual direction and psychotherapy facilitated my own redemptive journey, which I expressed in a painting called the Rainbow Crucifixion.

The Rainbow Crucifixion is an expression of my response to the violence and victimization of a traditional Christian theology of redemption that is focused on suffering and sacrificial death. The painting includes scenes of suffering and victimization that have touched not only my own life – as a survivor of child abuse, as a woman, and as a lesbian – but also the lives of millions of others. After the service, you may look at a print of Chagall’s painting, my painting, and a display about the symbolism in my painting.

As I prepared the paper that accompanied my painting, I learned that I was in good company. A number of feminist theologians have questioned the traditional Christian theology of redemption that is focused on suffering and sacrificial death. Mary Daly wrote that the sacrificial love and the “passive acceptance of suffering” of Jesus in the passion story are idealized as Christian virtues – the virtues of a victim. She pointed out that given the victimization that women already experience in a sexist society, these are not healthy virtues for women, and that encouraging these virtues to women only reinforces the “scapegoat syndrome” and plunges women even further into victimization.

Other feminist scholars have echoed similar perspectives by questioning the traditional perspective of sin as pride or self-assertion. They have suggested that such a definition of sin is the result of male normative assumptions that serve to only reinforce the self-denial and low self- esteem that has been all too often the heritage of women in a patriarchal and sexist culture.

Elizabeth Johnson, a prominent feminist Catholic theologian, wrote that the traditional interpretation of Jesus’ death on the cross as a requirement by God as the repayment for sin is “virtually inseparable from an underlying image of God as an angry, bloodthirsty, violent, and sadistic father.”

This is an image of God that was also questioned by Brock and Parker in their book, Proverbs of Ashes: Violence, Redemptive Suffering, and the Search for What Saves Us. In it, they discussed some of the traditional theological perspectives on suffering and redemption and suggested that such teachings are “inherently dangerous and destructive” for many Christians and especially destructive for women. They maintained that the Christian tradition will fall short in any promise of healing for victims of sexual abuse as long as it includes a theology of redemption that is focused on a central image of a divine parent who required the death of a child. This evaluation is consistent with my own experience as a survivor of abuse. Redemption by means of “divine child abuse” simply does not work for me.

I was also pleased to find that some of the feminist theologians who have challenged traditional Christian theology have developed new ways of thinking about spirituality. These theologians speak of the importance of relationship with God and with others in “right relationship,” which is based on mutuality, equality, respect, and friendship. Within such a theology, with its emphasis on right relationship, a new view of redemption was also born. These theologians reframed redemption as “healing in relationship” or as a reuniting a lover with a beloved who is desirable and valuable rather that one who is sinful or flawed. This is a view of redemption that not only makes sense to me intellectually, but it is a view of redemption that fits with my own spiritual and emotional journey of healing.

Along with a new understanding of redemption comes a new understanding of sin. Author and theologian, Rita Brock, suggested that one way to conceptualize sin is to think of it as “damage” — the damage that occurs in relationship, sometimes very early in our lives. She stated that because the damage occurs in relationship, then healing must also occur in relationship. After suffering prolonged and horrific damage in relationship (with my parents and within the Christian tradition), I have been blessed to find healing in relationship with my partner, with my therapist, and within Unitarian Universalism.

Much of the coursework and discussions in my classes at Loyola were useful in helping me develop a pastoral role that fits within the context of my work as a nurse practitioner. That is, in fact, exactly what I hoped they would do. What I did not expect was the powerful way that confronting a great deal of traditional Christian theology would prove to be the “sand in the oyster” that has eventually resulted in the “pearl” of my own unique journey of spiritual formation. It helped me to clarify and define my spirituality and to redefine redemption. I began to work through my understanding of redemption in feminist theological terms as healing in relationship with a God/dess who saw me as desirable and beloved, not as sinful and flawed.

For me claiming this redemption meant leaving the Christian tradition and returning to the Unitarian Universalist Church. I had decided to stop participating in my own oppression by being part of a tradition that involved the ritual repetition of a “scapegoat syndrome,” blood atonement theology of redemption as a central part of the worship experience. This was not the spiritual formation outcome that the director of my program, Father Kevin Gillespie, had anticipated. He was also not prepared for the depth of suffering he encountered in my painting, but to his credit did respond by saying it was indeed art and he did allow me to graduate.

In closing, there is one particular symbol in the bottom middle portion of the painting that I want to mention. It is one that is familiar to most of us here today. It is, of course, the flaming chalice — the symbol for Unitarian Universalism. It is included in the painting as a symbol of hope and as a symbol of my redemption. It is a sacred symbol to me that represents the light given to me as a child by my guardian angel “Elizabeth.”

Then as now I am aware of God’s love because – the light shines in the darkness and the darkness has not overcome it (to quote one of my favorite passages from the gospel of John). It represents for me courage, hope, the light of truth in the world, and the undying human spirit.

The Rainbow Crucifixion represents many things, not only in its symbolism, but also in its meaning for me personally. It is an icon for my journey of healing. It also stands as one way that I have said yes to life, yes to truth, and yes to love.

Please stand as you are able and join me in singing hymn #6, Just as Long as I Have Breath [to which the last line above is a reference].