— A sermon by Jaco B. ten Hove

— Paint Branch UU Church, Adelphi, MD

— April 9, 2006

READING INTRO:

The author of our reading this morning, Jim Wallis, calls himself a “public theologian,” which I think is an intriguing posture. He speaks at more than 200 events a year and turns up regularly in all major forms of media, addressing “the crossroads of religion and politics in America,” so I guess that qualifies as the presence of a public theologian.

The parallel role for us Unitarian Universalists might be Forrester Church, prolific author and senior minister at All Souls Unitarian Church in New York City, whose father was the notable senator from Idaho, Frank Church. Forest has been excellently active in the media, promoting liberal religion; his books and essays are stirring, timely and recommended.

But Jim Wallis is a progressive evangelical Christian, founder of both Sojourners, a nationwide network of similar religious folks “working for justice and peace,” and Call to Renewal, a national federation of faith-based organizations collaborating to overcome poverty by changing public policy.

His recent book, God’s Politics, has two subtitles, even: “Why the Right Gets It Wrong and the Left Doesn’t Get It” at the top of the jacket; and at the bottom: “A New Vision for Faith and Politics in America.” It’s a rambling treatise that nonetheless contributes a lot to this public discussion, especially as a qualifier to the burgeoning strength of the Religious Right. Wallis’s Christian credentials are impeccable, so his voice has impact. At least I hope it does, even if I disagree with him in significant ways.

Here’s a taste of his position, which will set-up my sermon to follow:

READING

adapted from God’s Politics, by Jim Wallis (Harper, SanFrancisco, 2005, pp. 346-47)

(T)he big struggle of our times, is the fundamental choice between cynicism and hope. The prophets always begin in judgment, in a social critique of the status quo, but they end in hope—that these realities can and will be changed. The choice between cynicism and hope is ultimately a spiritual choice, one that has enormous political consequences…

More than just a moral issue, hope is a spiritual and even religious choice. Hope is not a feeling; it is a decision. And the decision for hope is based on what you believe at the deepest levels—what your most basic convictions are about the world and what the future holds—all based on your faith. You choose hope, not as a naive wish, but as a choice, with your eyes wide open to the reality of the world—just like the cynics who have not made the decision for hope…

(And) let’s be fair to the cynics. Cynicism is the place of retreat for the smart, critical, dissenting, and formerly idealistic people who are now trying to protect themselves. They are not naive. They tend to see things as they are, they know what is wrong, and they are generally opposed to what they see…

They know what is going on, and at one point, they might even have tried for a time to change it. But they didn’t succeed; things got worse, and they got weary. Their activism, and the commitments and hopes that implied, made them feel vulnerable. So they retreated to cynicism as the refuge from commitment….

If things are not really going to change, why try so hard to make a difference? Why become and stay so involved? Why take the risks, make the sacrifices, open yourself to the vulnerabilities? And if you have middle-class economic security (as many cynics do), things don’t have to change for you to remain secure. That is not intended to sound harsh, just realistic. Cynics are finally free just to look after themselves….

(Cynicism can feed) what I call “secular fundamentalism” among too many of our liberal elites who seem to have an allergy to spirituality and a disdain for anything religious. In particular, they have such a visceral reaction to the formulations of the Religious Right that they make the mistake, over and over again, of throwing all people of faith into the category of right-wing conservative religion. That mistaken practice has further polarized the debate over religion and public life in America and has even deepened the impression among many Christians that the real battle is indeed between belief and secularism.

(However), the answer to bad and even dangerous religion is not secularism, but better religion…

SERMON

“The answer to bad religion,” according to Jim Wallis, is essentially this: Jesus, Jesus and more Jesus, mixed in with a leavening dose of the ancient Prophets. And, to his credit, I think, Wallis calls Christians to follow the religious, social and economic revolutionary Jesus—not the one who was later co-opted by authoritarians, materialists, absolutists and literalists, most of whom see only one way, theirs.

Such near-sighted extremism is partly what has inspired “bad” theology. Whereas Jesus was preaching and modeling good theology, according to Wallis, who urges a return to that anti-materialist orientation, especially an “option for the poor.” That’s what “better religion” looks like to him, and I applaud his clarity and courage.

Jim Wallis is a refreshing voice, evangelical but not fundamentalist—which is an important distinction to hold, because those two postures are not at all necessarily the same. If you are a Christian willing to release the materialism of our culture and honor the poor like Jesus did, Jim Wallis is your guy. He may be swimming upstream, even within Christianity, but he’s relentlessly, ethically, effectively on message.

And I enjoy listening to him, which I have done, sitting closer to him than I am to the front row now. He’s articulate, passionate but not flamboyant, persuasive, and prophetic, even— the kind of mouthpiece I believe Jesus himself would want. And I agree with him that the way to counter bad religion is not with less, but better religion.

However, I am not a Christian, never have been. I was raised Unitarian Universalist, with a large platform of possible religious paths underneath me, only one of which was Christian. But that call wasn’t loud enough and I forged my own way that includes some of the best of Christianity, I think, but stops short of being Christian, per se.

So I also have a different take on what “better” religion looks like, and I will be exploring this avenue here and more sermons over the next year. But meanwhile, I want as many followers of Jesus to join up with Jim Wallis as possible, because I think he’s got a grip on the authentic Jesus, more so than many other eager Christian mouthpieces, most of whom position themselves at quite a distance from that religious, social and economic revolutionary.

Have you watched Pat Robertson’s 700 Club lately? Here’s an amazing American figure, who drops the name of Jesus all the time, usually to serve his own very political and right wing agenda. He has become an almost comical caricature of himself, really; although it might be funnier if he didn’t command such a large and willing audience.

The 700 Club happens to come on each weeknight immediately after Who’s Line Is It Anyway, the improv show that frequently makes me laugh after a long day. So every now and then I’ll stick around to see what Crazy Pat’s up to. I did a study of televangelists when I was in seminary, watching a bunch of them fairly regularly for a while, and found it to be enlightening, in small doses.

So a few weeks ago I looked in on The 700 Club for the first time in a while, and quickly got quite a jolt. There, being interviewed by a friendly Pat Robertson in the very first segment was a member of my own high school rock and roll band (which, I have to admit, was named The Cult).

Turns out the guy on the electric organ who could really nail the Doors’ “Light My Fire” is now lighting Pat Robertson’s fire. He’s a very Republican expert and author on the subject of Iran and he was telling Pat everything he wanted to hear about what American policy toward that Islamic country should be.

It was pretty creepy and I watched with a cringing fascination, but I also wanted to be able to sleep that night, so I shut the two of them down mid-interview and tried to chase the icky image of this old chum of mine getting chummy with Pat Robertson.

But back to Jim Wallis, who is about as far apart from Pat Robertson on the Christian spectrum as you can get—religiously, socially and economically. Wallis offers a very important corrective to those who would lump all Christians into one basket and then toss the whole thing.

But he also falls prey to a very seductive trap that has most of us in its thrall as well. And I propose that getting us out from under this spell will be part of crafting a “better” religion for the post-modern 21st century. My endeavor from here on will be twofold: to name that trap and then begin to point in a positive direction.

I’m not, however, going to spend much time on a critique of what so-called “bad religion” is. Suffice it to say, as a Republican commentator [Kevin Phillips, former Nixon staffer and Reaganite] noted in a very insightful and critical piece, titled “How the GOP Became God’s Own Party,” in last Sunday’s Post Outlook section [April 2]: “Many millions believe that the Armageddon described in the Bible is coming soon. Chaos in the explosive Middle East, far from being a threat, actually heralds the second coming of Jesus Christ.”

Yes, this kind of theologically-based madness is out there, assembling allies all over our now very religious political landscape. It is called, among other things, Christian triumphalism, linked directly to a bald-faced strategy of “dominion” over the rest of us. And all this dangerous projection is theologically justified by some very talented religious leaders.

One suspects that until a different spiritual vision of the future begins to claim as much or hopefully more American inspiration, what Jim Wallis calls “bad religion” may just steamroll its way into even greater prominence, despite the irony of its idolatry. And certainly the Jews and Muslims each have their own versions of extremist politics based on dubious but somehow attractive theology.

Such religio-political extremism often avoids critique by adopting a fierce, intimidating, holier-than-thou mantle, but it deserves what challenges are slowly emerging. Wallis is doing his part, from within Christianity, and I pray that he gains momentum and attention for his worthy approach.

But, as might be expected, I take a different angle on what “better religion” might look like, although I can also accept the value of his vision, grounded as it is in an inspiration from the past. I’m less interested in deconstructing the nasty theology we both find distasteful and more interested in moving forward, expanding the wisdom of the past into a 21st century that offers new challenges and possibilities. I will start by raising what seems to me to be a foundational issue that informs our cultural worldview beyond the specific beliefs that are guiding some of our most misguided leaders.

The seductive trap that continues to enthrall most if not all of us moderns has a boring name that you’ve probably heard before: dualism, which itself is not inherently evil; we’re just overly dependent on its use, hooked on the rush it can provide. Dualism is now a trap because we get stuck in it. It has so pervaded our thinking that extremists get away with their narrow, self-serving agendas because we can’t seem to counter their dualistic appeal.

But even Jim Wallis uses a dualistic approach by posing [in the earlier reading] hope versus cynicism, as if it were a switch one could throw, on or off. Another important religious leader, Rabbi Michael Lerner, who’s right now actively trying to convene a progressive religious movement, is likewise also relying on a very familiar and accepted dichotomy. The title of his new, very provocative and helpful book, The LEFT Hand of God, completes the polarity with its subtitle: Taking Back Our Country from the Religious RIGHT [my uppercase for emphasis].

Lerner first provides a compelling analysis of “America’s Spiritual Crisis,” articulating why changing our current momentum matters. He does an insightful and thorough critique of how conservative ideologues and religious fundamentalists have been able to successfully commandeer so much political apparatus.

Then he goes further than most commentators and offers a stirring vision of what will unite the rest of us under a big, avowedly liberal religious tent. It is juicy reading, to be sure, laced with important—and original—challenges to our thinking and acting…but it still relies on a fundamental dichotomy, Left versus Right.

Dualism is bred into our psyches by a long established philosophical orientation that understands the world through pairs of opposites: either this or that. Such perspective may be a natural inclination, since much of the planet does seem to be generally organized in twosomes: night and day, hot and cold, up and down, male and female, etc.

But in the still emerging new paradigm of our evolving culture, many explorers at the cutting edge are finding that we just cannot automatically resolve—or even fully understand—many of the tensions of our time by positioning them on a line, either at or somewhere between two poles. Such a linear continuum, while a useful tool and a very ingrained orientation, is becoming less and less helpful—or true, even, when we try to grasp the complexities of 21st century existence.

Some couplings that have often been presented as opposites but now resist location on a linear continuum include: mind and body, science and the humanities, spirit and matter, secular and sacred, conscious and unconscious, etc. These and many more pairs of apparent or assumed opposites are proving to be very elusive if we try to fit their roundness into the square hole of a linear mindset.

Nonetheless, Wallis, Lerner and most other leaders still speak in dualisms—either this or that—because it’s still a persuasive technique; and it still hooks us. We respond to it because we’re taught to think this way. Listen for it and you’ll hear it everywhere.

But also found in the natural world is another organizing principle that has been largely overshadowed by the glare of Enlightenment logic, but may be rising in our collective awareness: the circle, with its repeating cycles that help us understand how things move in complexity and continuity.

Many of us are aware intuitively that circles are holistic and natural. However, they tend to minimize tensions, which can mean that they don’t get attention or have power that can be applied for gain. Circles have always been with us, they are comforting and creative, but not very political. Nonetheless, they hold an immense bounty of value, patiently awaiting and cooperating with our explorations, when we decided to notice them and their influence.

The ancient and circular Medicine Wheel with its multi-layered attributes; the six spherical directions; the four cyclical seasons—these are all obvious embodiments of this round wisdom, decidedly not dualistic. The planetary directions and seasons point to an even larger realm: the cosmos. There may be lots of intrinsic pairings on the Earth, but when you venture beyond our atmosphere, the dominant pattern there is circular (elliptical, round), with little reliance on dualism as a guiding, let alone dominating motif.

To me, this suggests that while pairs of opposites do abound and are very real, they are only a narrow representation of the whole, and not our best tool for understanding how the universe manifests in our lives and culture. Dualism pivots on the word “versus”; whereas circles have a center point. Which model seems like it would be more coherent with a positive future of peace and prosperity?

But over the past few centuries our Western rational conditioning has installed— hardwired—in us a strong bias toward automatically going to linear and dichotomous explanations for almost all inquiries. Heaven and earth, black and white, good and evil, active and passive—the list goes on and on and quickly the case is closed. We draw conclusion based on dualities.

Now, pairs of opposites are not bad, per se, of course. We are just out of balance by relying on them to explain everything. As the saying goes, “If all you’ve got is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.” But no one thinks hammers themselves are evil…do we?

I’ve become convinced that the dualistic approach is no longer automatically useful and is not going to help advance our consciousness any further. In fact, dualism, in its current dominance, can be an obstacle to a healthy future and, in some cases, we employ it at our peril.

For instance, an either-or attitude can easily create very powerful us-and-them scenarios, which in turn can be extremely effective in motivating support for self-aggrandizing and/or militaristic proposals. When this perspective is sanctioned as sacred, with overt religious justification, it can be doubly persuasive to a population that is only versed in dualistic thinking. And out comes the hammer.

A better religion for the 21st century will figure out how to transcend such simplistic and often stultifying choices between two poles. A better religion will guide us away from knee-jerk responses that urge us to just look for more enemies, and instead provide healthy underpinning for new models of unity within diversity, which is clearly a large challenge before us now. A better religion will give us options beyond paired opposites.

Watch yourself as closely as you can as you explain elements of your world, especially ones with some tension attached to them. I predict you will likely resort to using and justifying dualistic language. I know I do. I certainly don’t pretend to be cured of this conditioning. It’s what we’ve all been taught, here in the West, at least. It’s the water we swim in, unquestioningly. I expect to spend the rest of my life unlearning my reliance on this insidious thought pattern.

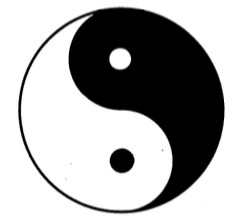

It’s interesting and instructive that Eastern philosophies are not nearly so beholden to linear models and approach the natural coupling of elements from a different angle, for instance the way the ancient Yin/Yang symbol is depicted.

Yes, it acknowledges two fundamental and opposite energies, but they are in direct relationship, in contact, even—not separate. And in fact they contain elements of each in both, held together in the shape of a circle. I find this to be a beautiful and powerful antidote image.

Separation is the key issue. Unlike the Yin/Yang symbol, linear models are not holistic, by design: they separate things, break them down into discrete parts. We have been taught to understand reality as a series of individual elements, with everything composed of independent building blocks. So when we use that dominant lens to perceive our world—what’d’ya know, we see separated elements.

I am convinced that things are just not as separated as they may seem. There is indeed some separation between things, especially at least as perceived in the visible light spectrum. But our scientists, at least, are telling us that before we leap to conclusions, we might want to try on more than one kind of lens, because there are interconnections we can’t necessarily see unless we go looking for them, using different angles.

Just last Thursday evening, for instance, Barbara and I attended one of the free public lectures in Goddard Space Flight Center’s series called “Eyes on the Sky,” and we learned a lot about NASA’s latest developments in imaging celestial bodies. The visible light band has produced some spectacular photographs, for sure, especially thanks to the Hubble Space telescope.

But once NASA put x-ray and infrared telescopes in orbit beyond our hazy atmosphere, we were able to “see” just how much more was actually out there that would never show up in the relatively narrow visible light spectrum.

In a parallel way, if all we look through is a dualistic prism that breaks everything into two poles, we will just see flat continuums and likely miss a big chunk of the grandeur of the natural and human ecology all around us, much of which is not at all flat, but interconnected in significant, even if not visible or linear ways.

But if we don’t intentionally develop lenses to open up that realm of reality, we’ll keep on perceiving everything as separate from everything else. We’re learning, ever so slowly, however, that life is indeed fundamentally connected and interdependent in magnificent, if mysterious ways.

Our UU Principles document first declared as much 20 years ago, with the Seventh Principle and the First Source. Those and the other primary statements of our religion are displayed each Sunday near the back of your Bulletin.

We affirm and promote “Respect for the interdependent web of all existence of which we are a part” [the 7th Principle:], which leads us to honor “Direct experience of that transcending mystery and wonder, affirmed in all cultures, which moves us to a renewal of the spirit and openness to the forces which create and uphold life” [the 1st Source:].

I believe this grounding affirmation of interconnection is a better path for religion to follow deeper into the 21st century than reliance on our dualistic and dichotomous training that has helped explain the world to us so far. There’s a whole lot of mystery and wonder to respect and explore.

After the Goddard lecture on celestial imaging, during the Question and Answer period, the speaker had to admit, any number of times, how much we still don’t know. That honesty is refreshing, and calls to mind Albert Einstein’s famous and wise observation that “We can’t solve problems by using the same kind of thinking that created them.”

I think we’re ready to wear new lenses that perceive the universe differently. In fact, if our species doesn’t get ready a little bit faster, even, it may not be much of an enjoyable future. There’s a lot at stake, as we evolve rapidly in technological power but slowly in consciousness.

I think Unitarian Universalists like you and me can help lead our kind into “better religion” because we are not beholden to an absolutist posture that is often seen dragging its heels, kicking and screaming into the 21st century. We at least affirm interdependence, even if we’ve yet to truly internalize it. We are thoroughly embedded in a dualistic culture, so I think we’ve got some more work to do to loosen up our own thinking and change our behavior in progressive ways. But I have great faith that we can contribute a lot, in our everyday lives, to a brighter future.

Progress, to my mind, is no longer about “onward and upward forever.” That inspires a rather linear image of basically one direction. I think it’s now more like “inward and outward together,” which means moving in all directions at once, with each person holding a piece of the truth, rather than just falling into line on a single path.

So one answer to “bad religion” can be to honor the emergence of a new kind of lens that first helps us identify where and how the limiting worldview of dualistic separation is in play; and then, without necessarily rejecting that, urges us to step beyond it, through it, into an articulation of what’s possible if we also see things in relationship, connected, cyclical, balanced together in a bigger picture, rather than only pitted against each other on a linear continuum.

Yes, there is separation on one level, but that’s not all there is. Come, let’s explore a bigger universe that connects us in ways we are just discovering. It won’t be easy, but what’s dominating right now ain’t so easy to take, either. A “better religion,” to my mind, is one of invitation, openness, inclusion and options, able to embrace “that transcending mystery and wonder” with loving patience and a center point of healthy balance.

I draw your attention to the classic box image of a vase flanked by two facial profiles; maybe you’ve seen this before. You can really only look at one at a time: either the light vase or the dark faces, but they are both there, together, interdependent. We choose the perspective that allows us to see one or the other, but we know they both exist. To the extent that we can see both at once, we are able to expand our vision. This is a grand metaphor, I think.

And with Emily Conover’s help, I added a top graphic to turn the vase into a Flaming Chalice, because I think we’ve got a darn good answer to bad religion here in Unitarian Universalism, and I’m eagerly looking for ways to deepen our grounding and express our faith. I encourage you to do the same. This expanded graphic reminds me that we can be powerfully, progressively centered amid multiple perspectives.

I think a “better religion” will persistently, faithfully resist settling for “either-or” explanations and instead build new muscles for exploring less obvious, “both-andian” paths. And I realize I should probably avoid my own dualistic inclination to set connectedness against separation. They are both true, in their way; what matters is that we put them in their proper context of relationship and balance.

But it is hard to stay out of the dualism trap, to not just keep pulling a hammer out of the toolbox and then go looking for nails. So we might need to ask explicitly: What else is in our toolbox to help us build a worldview for the 21st century? What else is in your toolbox?

The future beckons and invites our explorations and intentional movement toward a more peaceful and creative worldview, one that pivots on the knowledge that Our World is One World [which is the title of our inspiring Hymn #134…]