A sermon for Paint Branch Unitarian Universalist Church

January 29, 2017

The Rev. Evan Keely, Interim Minister

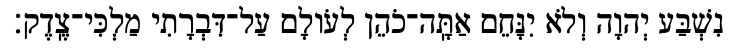

ADONAI has sworn, and will not change his mind:

you are a priest forever according to the order of Melchizedek.

PSALM 110:4

These ancient words from the canon of the sacred writings of Hebraic civilization speak to a universal phenomenon: in every human culture that has ever existed, certain persons have been chosen to fulfill a role that we would have to define, however loosely, as that of a religious leader. In every society, with almost no discernible exceptions, there appear to be certain roles that have always been fulfilled by someone: the ruler, the warrior, the farmer or rancher, the merchant, the caregiver, and the religious leader. In all of these roles we can distinguish some function related to survival, roles that relate to organizing the community, defending it from threats, producing food and shelter and caring for the vulnerable — these necessary functions are apparent in each of these roles, with one great exception. A priest, a sage, a religious leader is not in any obvious way indispensable to the community for the maintenance of its existence. How do we then explain that this role comes into being in just about every human culture that has ever been, from prehistoric times up to the present moment? We could argue that in the twenty-first century, not everyone has a need for a religious leader, but the fact of the matter is, Paint Branch Unitarian Universalist Church has always had one. A minister is not indispensable to the continued survival of this institution, and yet I am not aware of any extended period of time in which this organization, of its own deliberate choice, has dispensed with having a minister. From its earliest days back in the 1950s, as soon as it was feasible, this congregation got itself a minister, and that chain of professional religious leadership in this organization has remained unbroken for six decades. I have never heard anyone in this church ask the question, “Why do we have a minister?” I am aware of only one person who has asked the question, “What would it be like for this church to not have a minister?” — and that person was myself. I am not advocating for not having a minister or for having one; I ask the question to provoke us to think more deeply about something which is so familiar to us that we may not always reflect on what it might mean. We might be genuinely baffled by the question. Some might even be uncomfortable or even downright irked by it: “Well, of course we should have a minister! What else would we do?” If those are among the reactions to the mere question, that in itself might tell us something about the role of the minister in this community that is Paint Branch Unitarian Universalist Church.

The passage from the Psalms about “the order of Melchizedek” is mysterious. It seems to refer to a very short and rather cryptic passage from the fourteenth chapter of Genesis, in which Abraham is blessed by “Melchizedek, King of Salem… priest of the Most High God.” The ancients tell us next to nothing about this Melchizedek, which perhaps adds to his mystique and his allure as a wise and powerful being who seems to exercise both temporal and spiritual power. There is something of the eternal in him, something ineffable and elemental about this priestly role. The enigmatic Melchizedek seems to represent the singular capacity of the religious leader: the priestly figure is someone who does something (or some things) that no other person can or should do. We can see examples of this in any community that has a religious leader. In Unitarian Universalist congregations (including this one), the minister does at least one thing that no one else does: week after week, the community gathers on Sunday mornings, and much of the time, everyone expects that the minister will stand up in front of everyone, perhaps wearing funny clothes that no one else wears, and speak uninterrupted for about twenty minutes. We just accept this. It is an odd ritual if you stop and think about it, but generally we neither stop nor think about it. Unitarian Universalism is by no means unique or even exceptional in this regard: religious leaders in many different faith traditions regularly deliver a sermon (or a homily, or a dharma talk, or a platform, or whatever else it may be called). Unitarian Universalists are also not unique in placing a very high value on the word, the written word and the spoken word; ours is a very verbal religion. So it says a lot about us that we expect a religious leader to make these weekly offerings of spoken words, and that we sit and listen to the spoken words, we don’t comment immediately afterwards (indeed, most listeners scarcely comment at all), and we move on. This congregation is willing to commit a significant chunk of its annual financial resources for this role to be fulfilled by the same individual week after week. This church could save a great deal of money by deciding to give up on this: fifty-two very generous stipends for fifty-two different guest speakers over the course of a year would cost a lot less than salary and benefits for a full-time minister. I am not proposing that this church do that or not do that; I simply offer this paradigm of a very different scenario as an illustration of the mysterious power we invest in our ministers.

To be sure, preaching sermons is not the only thing we expect of ministers in a Unitarian Universalist congregation like this one. There is also the matter of pastoral care. When we hear the phrase “pastoral care,” we often think of very specific things: a minister visiting a congregant in the hospital, a minister meeting privately with a congregant who is having a personal problem and has asked to meet with the minister for counsel. These are certainly examples of pastoral care, but we also know that there is the broader sense of it, the idea that the minister’s presence and conduct are signs of caring. This is of immense importance to congregations, as well it should be, even though it is next to impossible to define in any decisive way exactly what a caring presence is or is not. We think we know what this looks like, but if we are honest, we recognize that the baffling complexities of human behavior often defy any easy understanding. An extreme example would be the Reverend Jim Jones, the pastor of the infamous Jonestown congregation in Guyana. The very name Jonestown is synonymous with horror and the worst excesses of congregational sickness — and rightly so: one could argue that that was the unhealthiest congregation ever; participation in that faith community was almost uniformly fatal. Yet Jim Jones was known by his followers as a caring pastor. Of course, in truth he was a deeply disturbed, evil man who brilliantly and cruelly manipulated his followers into committing unspeakable enormities, but from the survivors of that catastrophe, we know that he was perceived as caring. How else could he have persuaded all those people, nearly a thousand of them, to throw away their freedom and their very lives? I am not aware of anything even remotely analogous ever happening in a Unitarian Universalist congregation. But I am aware that many congregations in our denomination have shown themselves over the years to be more than willing to abide in their embrace of clergy leaders who were actually very troubled individuals who engaged in terribly destructive behaviors. Among Unitarian Universalists today, especially among those of us in our clergy, there is a coded shorthand we use: we say, “It was the sixties and seventies,” referring to those decades of the twentieth century in which a chillingly large number of our Unitarian Universalist ministers (no one knows for sure how many) engaged in profoundly hurtful, irresponsible sexual misconduct. A few of the very worst offenders were here in the metro-DC area. Decades later, some of our congregations are still doing the work of healing and restoring trust. But part of what made those abuses possible is that the offending ministers were often highly charismatic persons who were perceived as very caring pastors, not to mention that many of them were also highly regarded for their preaching. I wish I could say that those problems have disappeared from this denomination, but while they have not, things are much better today because there is far less of a willingness to look the other way. And we know that these kinds of abuses, unfortunately, are by no means unique to this denomination. All this is to emphasize the point that while we think we know what a “good minister” looks like, the truth of the matter is, the intricacies of human personality make it easy for us to deceive ourselves.

If there is any history of clergy misconduct in this church, I have heard nothing about it. To the best of my knowledge, Paint Branch Unitarian Universalist Church has dealt with the vicissitudes of the more commonplace blessings and challenges that unfold between ministers and congregations. Questions abound: who has power and authority in this organization? How is it exercised? What do we do when we disagree? How do we make decisions? How to we deal with conflict creatively and constructively? These are the kinds of questions that healthy congregations openly ponder and explore and discuss. These are the kinds of questions that have been vital to this two-year period of intentional transitional ministry, now about three-quarters of the way toward completion. One of the things we’ve explored is the ancient story of the Golden Calf: back in the fall, we contemplated together the many meanings of this old tale, and one of the things we wondered about together was what prompts the people in the story to give up on the things that are of greatest value to them and to instead focus their devotion onto something of lesser value: the Israelites abandon the God who has delivered them out of their oppression, and bow down before a golden statue. The statue has value: it isn’t made of garbage or ashes, it’s made of gold, something valuable and useful. But gold isn’t as valuable as the people’s sense of identity and purpose, their core values of community and communal meaning-making. When I think of this story and what it might mean to Unitarian Universalists, I am reminded of a remark once uttered in my hearing by the Rev. Peter Morales, the current President of the Unitarian Universalist Association: he said, in effect, that amongst ourselves, we Unitarian Universalists can sometimes be really good at disempowering everyone and then calling it democracy. We do, in fact, value personal freedom and individual autonomy. Those are good things for us to value. The point is: do we sometimes place supreme value on our individual preferences over and above the value we place on community? If we do, how do we see signs of that in our relationship with ministers?

Every community has ins unwritten, unspoken and unconscious expectations. Those expectations cover pretty much every aspect of communal life; in a church, it’s not just about the minister and the minister’s role, but certainly the minister is affected by these secret rules. In some churches, there is an expectation which is not only unwritten and unspoken, it is even largely unconscious, and that is this: if the minister really loved us, she would know what we want without our having to tell her, and if the minister really loved us, he would give us what we want without ever questioning whether or not what we want is what’s actually good for us, without even ever questioning whether or not what we want is even actually doable by any mortal being. I wonder if this springs from a desire to place individual autonomy and personal preferences over and above communal relationships.

This summer, this church will have a new minister. The great hope is that the ministerial search committee will present a candidate to the congregation in the spring, the congregation will enthusiastically vote to call that minister, and that minister will joyously accept. That would be great outcome. It is certainly not the only possible outcome; do we assume that it would be the best outcome? Would it be better than a third year of interim ministry with a new minister, or having a developmental or contract minister, or a part-time minister, or no minister? It’s not up to me, nor should it be. But I wonder what we would learn about our expectations of religious life, of one another, and of ourselves if we openly explored together the questions about what clergy leadership means to this church and what different possibilities might look like for this church and its future.