for Paint Branch Unitarian Universalist Chuch Adelphi, Maryland 3/19/2017

Van Summers, Worship Associate

Each of us has to make decisions about the charitable giving of our time and money to do good in the world. This morning I’d like for us to think about the thinking we do in making those decisions. I’ll start by describing two different types of thinking we do every day. They have been referred to as thinking fast and thinking slow.

I’ll give an example of each.

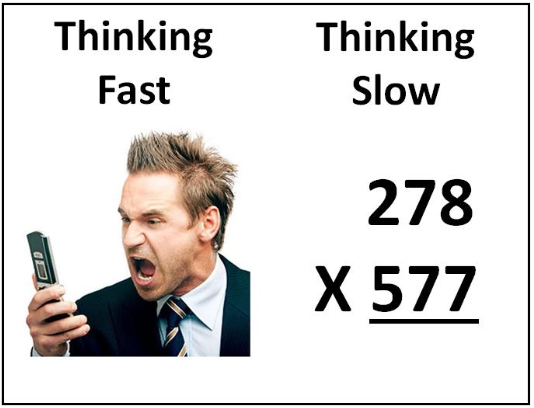

First I’m going to show you a picture of person and I want you to look at the picture and just notice your thoughts while you look at it.

I think many of you probably think the man in the picture appears to be angry or upset or both. And that he was probably shouting into the telephone. And you may even have ideas about some of the words he was using.

Did you choose to think through what the man might be feeling and thinking or did those ideas just seem to arrive?

This effortless and rapid and involuntary thinking is an example of the “Fast Thinking” I mentioned earlier.

We often rely on this type of thinking in our lives and that can be a very good thing in many cases, but not always.

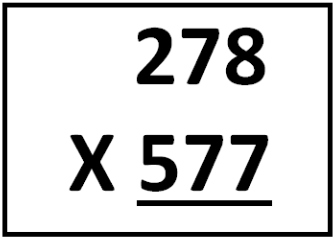

Now for a problem where fast thinking won’t get the job done, where the answer is not going to simply arrive.

The answer to what is 278 X 577 does not arrive effortlessly. The “slow thinking” required in this case differs from fast thinking because time and effort is needed to solve the problem and you have to choose to invest that time and effort or the slow thinking doesn’t happen.

We engage in these two very different types of thinking everyday and I want to relate this to the thinking we do in making decisions about charitable giving.

Let me switch to an example that involves altruism and giving.

I want to quickly describe a research experiment I’m going to call the Rokia and Moussa study.

There are three conditions in the experiment and you get assigned to one of these three.

Whichever condition you are in, you begin by doing a task that you are paid for. So have some extra money before you move on to the next part of the study, where you are put in one of the three experimental conditions.

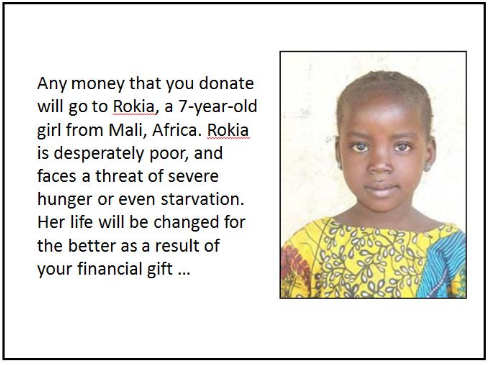

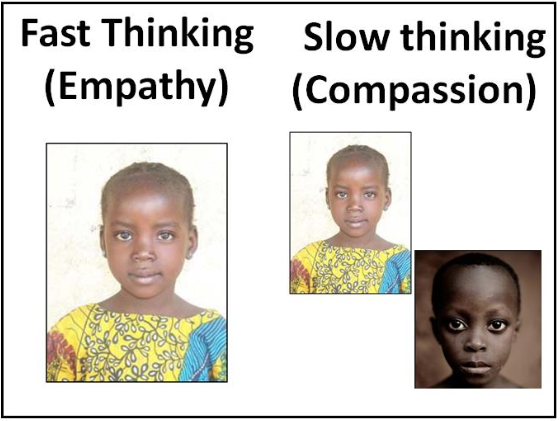

If you are assigned to the Rokia condition you would see this picture and read this text:

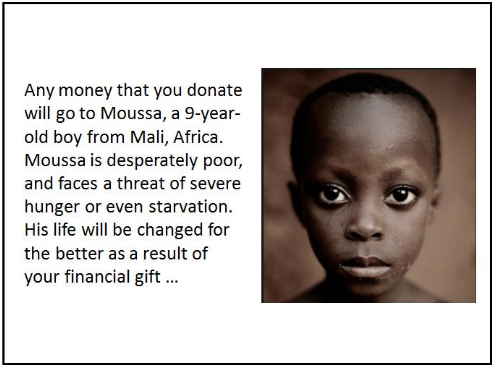

In the Moussa condition the picture is changed and the text is about a 9-year-old boy instead of a 7-year-old girl:

In the third condition, the Rokia + Moussa condition, you see both pictures and the text is changed so that you are asked to donate to save both Rokia and Moussa.

Regardless of which condition you’re assigned, you are asked:

- If you are willing to donate and how much

- How positive or negative your feelings are about donating

- How probable you think it is that your donation will make a real difference

The surprising result is that people were likely to give more if they were in the Rokia condition or in the Moussa condition than if they were in the Rokia + Moussa condition.

And the reason does not appear to be that you think you’ll make more of a difference in one of the single child conditions than in the two-child condition, it’s the more positive feeling you have about donating.

The greater giving to the one-child conditions may be an example of fast thinking – the thinking that flows out of us effortlessly and quickly.

We are more able to feel empathy for a single person than for two people and certainly more than we can for 100 or 100,000 people. Each of us is more able to identify with being a starving child than with being two or 100 starving children.

It is a challenging idea, but perhaps relying on empathy, our ability to put ourselves in other’s shoes, may not lead to the best decisions about how to do good in the world. Empathy causes you to zoom in on a single individual like a spotlight. You’re also more likely to feel empathy towards someone more similar to you than someone who is different, someone in front of you more than someone you are not in direct contact with, someone you find more attractive than someone you don’t.

Compassion is sometimes thought of as another word for empathy, but it is a different thing. Compassion is caring for others, hoping that they will thrive and be happy, loving them and wanting only good things for them. Compassion is not being in their shoes or feeling their pain.

One way of describing the difference is that suffering in the presence of suffering is empathy while loving in the presence of suffering is compassion.

Feeling compassion towards others, particularly those who differ from us, may not flow out of us as naturally as empathy towards members of our group. So it may require more focused effortful thinking than empathy. But if it leads to more good in the world, the slower thinking required for greater compassion may be worth it.

There actually is a way to move compassion toward becoming faster and more effortless – toward fast thinking. That is through practice. If you practice loving kindness meditation you spend time focusing your mind on wishing others well, hoping they are happy and that they thrive, hoping no harm or bad fortune comes to them. These good wishes are directed not just toward friends and family but to those we hardly know, to those we know who may be the opposite of friends and to those we only know about indirectly.

I don’t know how many here this morning practice loving kindness meditation but I know Beth Charbonneau has been practicing it for about 20 years and I think you would probably agree that Beth is quite a bit more awesome than some of the rest of us.

So if fast thinking and intuition may not be the best ways to make decisions about giving to do the most good in the world, how do we do some good slow thinking relating to altruism and giving?

“Doing Good Better” is a book by William MacAskill who is a professor of philosophy at Oxford University. He is the co-founder of the “Effective Altruism” movement that advocates some slow, hard thinking about where we direct our giving to do the most good.

His book is essentially a primer on the ideas underlying the Effective Altruism movement.

Many of you know I’m a member of the Quest Book group here at Paint Branch and last time we were choosing our next book I suggested we read “Doing Good Better” but it got voted down.

But honestly, what does the Quest Book Group know?

MacAskill suggests there are five key questions we should ask when we consider how to direct our time and treasure to do the most good.

1. How many people benefit and by how much?

Here we are asked to think concretely about the likely benefit to people’s lives of various choices so we don’t squander our time or money on things that don’t do very much to make people better off. To know how much benefit the giving you do is likely to produce, you need to have an idea of how many people will benefit and how much benefit they will receive. It sounds like a tall job to estimate the real-life benefit of a particular charitable gift but there are reasonable ways to make these sorts of estimates as MacAskill’s book explains.

2. Is this the most effective thing I can do?

The idea here is to spend time and money not on merely good activities but on the best ones. So this is a straightforward extension of #1 and just means that you’ll be comparing expected benefit across available alternatives.

3. Is this area neglected?

One thing that can make your giving more effective is to give to a cause that is receiving little attention. This may be where your help can make the most difference.

4. What would have happened otherwise?

Avoid good works that would happen anyway. This obviously relates to #3

5. What are the chances of success, and how good would success be?

This one relates to thinking about uncertainty correctly. Activities with low odds of succeeding can still be attractive places to donate if the payoff is high enough. The thinking described above clearly requires time and effort – before giving your time and money you are asked to estimate how many people your giving will help, how much it will help, and how that benefit compares to the likely benefit of directing your donation somewhere else. Thankfully there are organizations whose mission is to examine and try to answer these questions.

Givewell.org is one organization that does extraordinary in-depth research to determine which charities do the most good with every dollar they receive.

Along with thoroughly describing their analyses and decision-making process, they regularly update their list of most effective charities.

I guess it’s pretty clear that I highly recommend William MacAskill’s book about doing a better job of doing good. It is well written and contains a range of ideas that may challenge your current thinking on these issues. Doing our most to be effective at doing good in the world requires some slow, careful thinking. Think twice at the very least!